This is the most perplexing labor market in our lifetimes. It’s unclear if there are too many workers or too few.

“Help Wanted” signs are everywhere, but the most recent “jobs report” stated that 7.6 million Americans are unemployed and millions more are underemployed (i.e., you have a really miserable job for which you are way over-qualified).

This problem, which some think is another by-product of the pandemic, is not new. Almost three years ago, we wrote:

The labor market continues to strengthen as new jobs are added and unemployment hovers around its lowest level in fifty years. Over the past few years, workers have become more and more scarce. You may have noticed retail shops in your area closing down for periods of time solely because they can’t hire enough people to stay open.

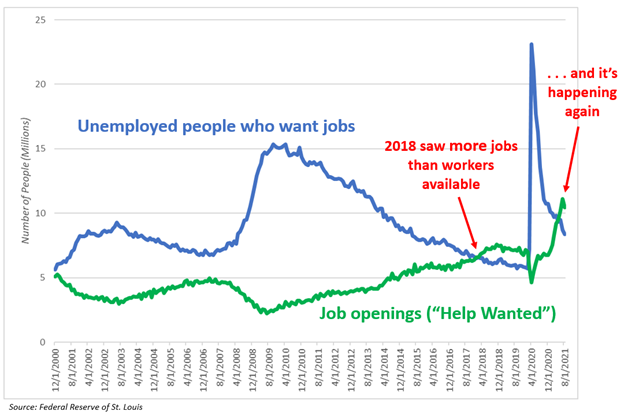

In 2018, we began to see a trend that we hadn’t yet seen in this century. There were more jobs available than people willing to fill them.

The pandemic temporarily reversed that trend (with massive immediate but temporary unemployment), but it is now occurring again.

Why? No one really knows the exact cause, and there is likely not just one culprit. But demographics are certainly one reason.

As Baby Boomers matured over the past fifty years, the workforce expanded. Several years ago, that generation finally began to face its retirement years. And it’s possible that the pandemic accelerated the transition to retirement for some Baby Boomers.

While the cause is mainly demographic, so is the fix.

- Go back 25 years and have more babies? Without the DeLorean, this option is off the table.

- Loosen immigration policies? Politically fraught, but a real possibility. And maybe someday a necessity.

- Entice more people to return to the workforce? As we mentioned in August, three million people left the labor force during the pandemic. Did these people retire? Stay home with their kids? Go back to school? Decide to live on less? We don’t know for sure, but there is a supply of people that worked “pre-pandemic“ that could probably be tapped given the right incentives.

As an aside: Don’t let the post-pandemic explosion in job openings (green line in the graph above) fool you. The pandemic did not create a bunch of new jobs. There are actually fewer total jobs in America in today. There are simply more open jobs. This is a by-product of those people who left the workforce entirely.

The dearth of workers isn’t just a local problem, making it hard to order a latte at your neighborhood coffee shop. It also has far-reaching effects on the global supply chain . . .

__________________________________________

In a month or so, you may discover that the special gift/toy you want to purchase for the holidays is unavailable.

Unavailable anywhere.

Not in stores. Not online. Not anywhere.

Kind of like toilet paper 18 months ago.

But this time it won’t be because of consumer panic. This time it will be because the “supply-chain Grinch” stole Christmas.

For many years, we have taken it for granted that a product manufactured in China will arrive on our department store shelves forthwith.

This process was never really that easy to begin with, but it has become exponentially more difficult today.

Cargo ships and trains and trucks and warehouses and distributors and retailers are all part of what we call the “supply chain.” And American shoppers have become so spoiled by a supply chain that has run so smoothly and seamlessly for so long, this holiday season could be a major wake-up call.

The initial result of COVID lockdowns 18 months ago was a drop in consumer demand. The re-opening of economies, in combination with governmental subsidies to consumers, caused an unprecendented increase in demand.

The unintended consequence of all that is massive bottlenecks at our major port cities (Los Angeles, Long Beach, Miami, etc.) where container ships are unloaded (and loaded).

This supply-chain disruption has caused an increase in prices. The lack of available workers has caused an increase in wages. And an increase in prices combined with an increase in wages is inflation, right?

Well, yeah, kind of. But nothing like the inflation of the ’70s, a decade that ended with double-digit inflation and double-digit interest rates.

The 30-year U.S. Treasury Bond paid 15.19% in September 1981 because inflation was running around 13%–14%.

So if the U.S. is expecting continued drastic inflation, why is the bond market not paying any attention? Why are U.S. Treasury Bonds paying only 1.94%?

At BCWM, we think the bond market is telling us that yes, we will be experiencing inflation for the next year or so. But once the supply-chain disruptions have disappeared (and they will . . . eventually), we will be looking at a rough (slow) economy which will take care of the “too many jobs and not enough people” problem.

We continue to look for low interest rates long term.

This information is provided for general information purposes only and should not be construed as investment, tax, or legal advice. Past performance of any market results is no assurance of future performance. The information contained herein has been obtained from sources deemed reliable but is not guaranteed.